The recent NUSS Professorship Lecture: Future of Learning with Professor Manu Kapur challenged participants to ‘unlearn’ conventional learning and teaching methods.

Over 500 participants attended the latest instalment of the NUSS Professorship Lecture series held on the evening of 21 April 2021. The hybrid event was a momentous event for the Society — it was the first Professorship lecture since October 2019 (before taking a long hiatus due to the pandemic) and was the first of its kind and comprised invited guests present on-site at the Kent Ridge Guild House and virtual attendees who connected via Zoom. Led by Professor Manu Kapur, Professor and Chair of Learning Sciences and Higher Education at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, the lecture served as an introduction to his breakthrough research on Productive Failure.

Mr Ng Teck Wee, Co-Chairperson of the Intellectual Pursuit & Lifelong Learning Sub-Committee, hosted the event while Mr Edward S Tay, President of NUSS led the welcome address. Dr Patricia Chen, Assistant Professor for the Department of Psychology, and Deputy Director of the Institute of Applied Learning Sciences and Higher Educational Technology at NUS had the honour of introducing the evening’s esteemed visiting professor.

When Prof Kapur took the stage, the multi-faceted educator shared that the night’s event was the first talk he has given in person in a long time since the pandemic hit and was raring to kickstart the spirited session. Here are the key learning points from Prof Kapur’s lecture.

Different levels of learning require different methods

“To understand the future, we must first understand a little bit of its history.” Prof Kapur opened his lecture by going through the different levels of learning — neural, cognitive, social, and cultural — all of which play significant roles in learning and retaining knowledge.

He pointed out two critical factors that can influence these levels — time and method. “Learning can occur in just milliseconds or across years (as seen in enculturation), and methods that help you acquire knowledge may not be the same method that can optimise social participation and enculturation.”

The goal of teaching is to activate prior knowledge

According to Prof Kapur, the first job of teaching is not to teach but to prepare the pupil to see what you want them to see. This addresses the first concern that students have — they fail to see what their teachers are seeing.

In order to work around this, educators must tap into and activate the students’ prior knowledge to prepare them to receive new information. Once activated, encoding new information becomes easier and integration becomes more seamless, allowing students to understand better.

Knowledge is tied to doing

“Everything we know is situated in what we are doing, and ‘doing’ can be thinking, reflecting, discussing, designing, building or even questioning.” Prof Kapur explained that the reason why people fail to transfer knowledge or information successfully is the misalignment in the context of ‘doing’ in school and the kinds of ‘doing’ at work and later on. He added that these do not have to be perfectly aligned but the greater the overlap between the ‘doing’ at school and at the application stage, the higher the success of learning, transfer and retention of knowledge.

It matters how you are taught

Prof Kapur went on to discuss how the development of creativity is path dependent, which means how you learn new knowledge can influence how creative you can be with that knowledge. He demonstrated this by comparing two methods — Direct Instruction (DI) and Productive Failure (PF).

In DI, you are given instructions first then tasked to solve the problem. It’s the most dominant and straightforward method that most are already familiar with. Applying PF reverses the order — the problem solving comes first followed by instructions.

While both approaches worked well when applied to basic knowledge such as the type of knowledge that comes out on standardised tests, the PF method scored higher in conceptual understanding and transfer or the student’s ability to be flexible with what they have learned and apply that to solve more advanced problems. In most cases, PF students performed as if they are a year or so ahead of their peers following the DI method.

Applying the Productive Failure model to teaching

Using findings from his research, Prof Kapur shared how he structured the PF model to be deliberately designed for failure to encourage students to learn more, under the guiding thesis of “The more they failed, the more they learned.” When students are made aware of what they do not know or cannot solve, they begin to be more interested to learn the solutions and are more prepared to receive new information or knowledge. Upon applying the PF method in small doses across 166 experimental groups, results showed that PF students acquired three times more knowledge than their DI counterparts.

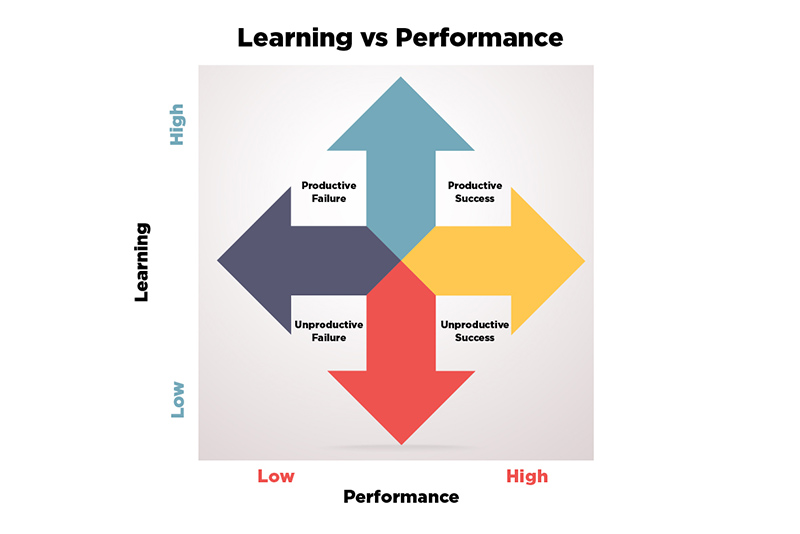

Learning and performance are not the same

“Just because students perform well in a test does not mean they really understand the material.” To illustrate this, Prof Kapur shared a simplified diagram that shows the learning and performance spectrum. Educators and students can aspire to reach Productive Success, where both learning and performance levels are high. He also pointed out the illusion of high performance but low learning, which gives rise to Unproductive Success, which he believes affects education most.

Prof Kapur continued his talk by discussing how artificial intelligence can help higher education discover new effective methods to teach, and how the new teaching methods that they are developing aim to bridge the gap between explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge.

The last part of his lecture included a lively Q&A session where Prof Kapur answered about 20 questions sent in by both on-site and virtual participants. Topics discussed included PF’s impact on culture and how it can help on a national level, how to incorporate and structure PF within a curriculum or in parenting, and how to replicate PF on a purely virtual platform.

Subscribe to the NUSS YouTube Channel and stay tuned for the highlights on Prof Kapur’s lecture.